Jersey City Sports History: Boyle's Thirty Acres

Jersey City has a long and rich history when it comes to sports. In particular, the city has been home to some of the most iconic boxing matches in history. On July 2nd, 1921, Jersey City hosted a match between Jack Dempsey and Georges Carpentier that is still considered one of the most important bouts ever fought. That match was followed by Boyle's Thirty Acres - an arena that was once home to some of the most legendary sports figures in history.

Boxing promoter George “Tex” Rickard, knew that bringing his client, world heavyweight champion Jack Dempsey, 26, into the ring to defend his title against world light heavyweight champion Georges Carpentier, 27, would draw a big crowd. But he faced the challenge on where to host the epic match, that is until Mayor Frank Hague built him an amphitheater, the largest at the time, in the heart of Jersey City, New Jersey.

“In making the rounds of the cities which he has named as the possible sites for the Dempsey-Carpentier fight on July 2, Tex Rickard yesterday paid a visit to Jersey City where he was the guest of Mayor Frank Hague at a luncheon at the Elks' Club, Jersey City." - New York Times, April 1921

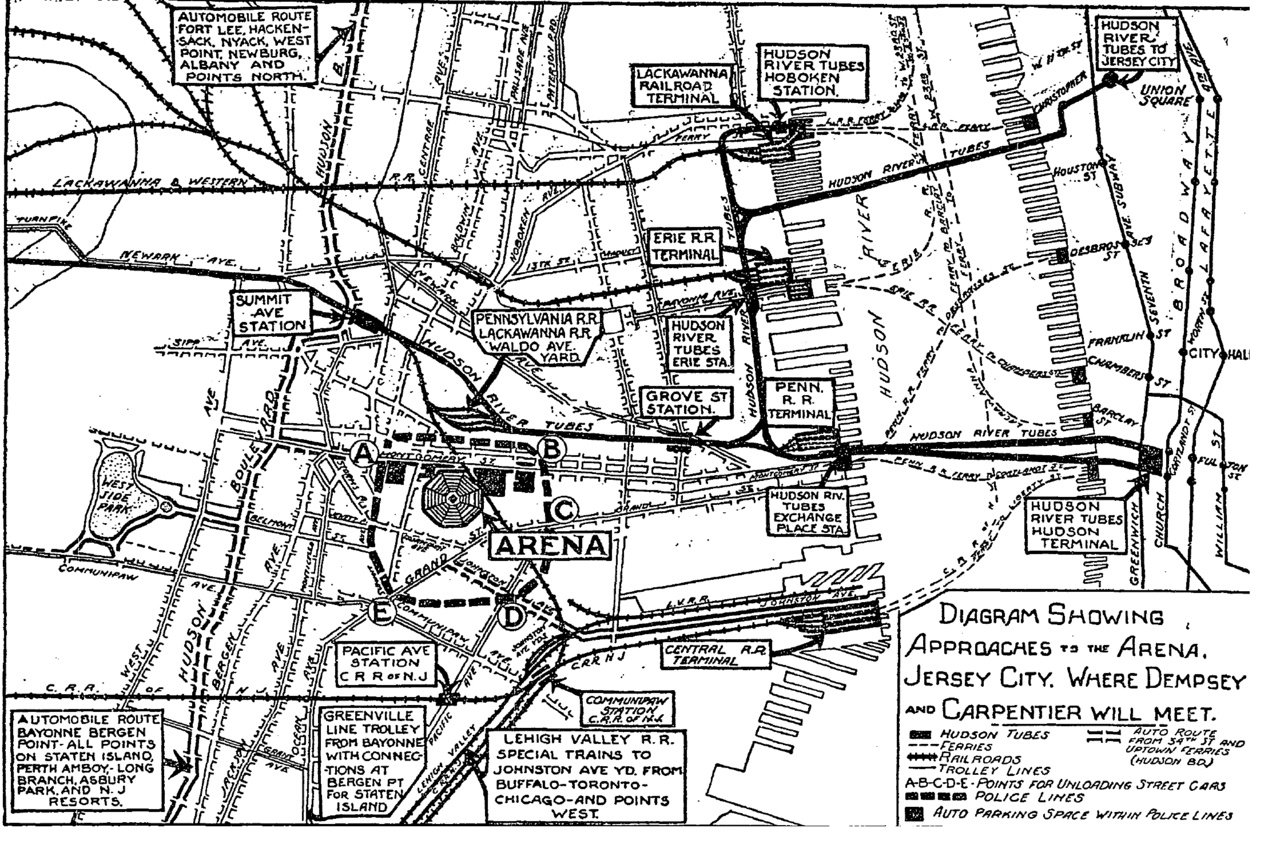

With seating promising to originally hold 50,000 people, Rickard decided to forgo his usual venue, Madison Square Garden, to accept Hague’s proposal to build a new amphitheater just for the event, a work around to the bit of trouble he had recently faced with the New York State Boxing Commission.

A Jersey City Farm becomes the largest Amphitheater of its time

In the 1890s the field called Montgomery Oval had been the home of a Jersey City baseball team in the old Eastern League. But by April 26, 1921 when Rickard walked onto the neglected land that Mayor Hague was pitching him, it was nothing more than a section of swampland in the middle of Jersey City, so recently filled in with garbage that it was still cluttered with rubble and refuse, tin cans, glass, and broken boards.

It was out of that rubble in the course of only two months that Boyle's Thirty Acres, a stadium that became known to the world as the site of the second-best boxing match in history behind David and Goliath, was built.

Bad Guy vs Good Guy, Dempsey and Carpentier square off.

The fight itself was a product of the times. The Great War had ended three years earlier and Jack Dempsey, a respected elder statesman of the ring and a jovial Broadway host, was charged with draft dodging, condemned by most for not having "done his bit" in the armed forces. Georges Carpentier, the Orchid Man,

the First Citizen of Lens, was a natural hero. Wounded twice during the war and decorated with both the French Médaille Militaire and the Croix de Guerre with palm Carpentier was the idol of all women. The fight was credited as the first boxing match in which women were allowed to attend. "I hope Carpentier wins," people said, "but I'm afraid Dempsey will knock his block off." Rickard, determined to put on an epic show, fed the press the narrative of a fight between the handsome French war hero, Carpentier, and the American draft dodger.

The fight was a glaring mismatch, but spectators were so engrossed in the emotionally charged battle of "good guy vs bad guy" that Carpentier's mediocre record and light-heavyweight body (a frail-looking 172 pounds against Dempsey's 188) seemed almost unnoticed. The New York Times cast the Frenchman as not only the representative of his country but of the "millions of soldiers who had fought in the trenches."

As part of Rickard's strategy to keep his client's allure, he cloaked him in secrecy. Reporters were not allowed into Carpentier's training camp, where he was rumored to be working on a "secret punch." Rumors spread that Carpentier's coach, Descamps, had a curse that had made previous competitors, such as Bombardier Billy Wells and Joe Beckett, feel "uneasy with that man staring at me," Wells claimed. "I felt queer all over, even before Carpentier struck the first blow," said Beckett. Even during the week of the fight, a Paris newspaper, Le Petit Parisien, suggested that Descamps be forced to wear opaque motorcycle goggles "through which the malevolent emanations would not pass."

Along with the growing pile of press clippings, ticket orders and money poured into Rickard's office. Over $100,000 was raised even before the site was announced, $650,000 with one month left, and $1 million five days before the match. The match became the first 'million dollar gate' in boxing setting a then record of $1,789,238. Historians credit the fight as a key landmark for the Golden Age of sport that boomed during the 1920s.

People around the world were preparing for what was now being called the Battle of the Century. The fight caused the cancellation of a baseball doubleheader between Jersey City and Newark. The City of Paris waited for the lights on a plane flying overhead to tell them who the champion would be - red for Carpentier, white for Dempsey. As other planes waited near Jersey City to fly pictures of the fight to Chicago for the next morning's Tribune, ships docked on the Hudson River were ready to transport to Europe. People everywhere prayed that right would triumph over might and that Carpentier the "Hero" would defeat Dempsey the "Villain." The winner getting $300,000. The loser, $200,000.

The building of Jersey City’s Boyle’s 30 acres

In the meantime, the workmen were working their own miracle on Boyle's Thirty Acres. By mid-May, the land had been cleared, 60,000 cubic yards of earth had been removed, and the all-wood octagon had begun to rise. The capacity was changed from 50,000 to 70,000 and again to 91,613. As plans expanded, construction costs doubled from the original planned $125,000, leaving the 500 carpenters and 400 laborers scrambling to find the 2.25 million board feet of lumber needed to complete the job. One of the workers said, "Ticket sales were so good, we had to keep adding." With the greatest seating capacity of any amphitheater at the time it was built, the final numbers were not stenciled on the seats until the night before the fight.

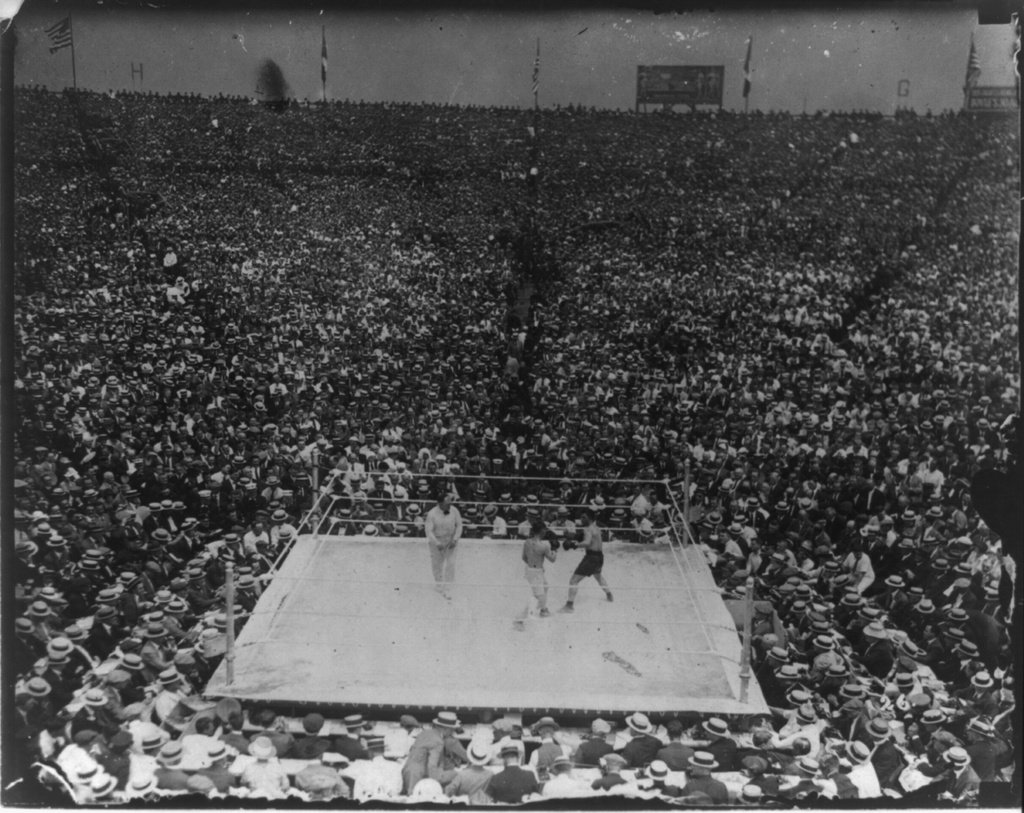

Most came by subway and buses. The famous names, however, arrived in limousines and private railway cars, yachts and chartered tugboats. William H. Vanderbilt. John D. Rockefeller Jr. Henry Ford. Harry Payne Whitney. Vincent Astor. George M. Cohan. Jake Ruppert. And Al Jolson, who had closed his show in Butte, Mont, so he could attend. Celebrities sat front and center in the $50 ringside seats (folding chairs brought over from Madison Square Garden). Behind them, on benches of spruce, sat the masses of people who purchased tickets ranging in cost from $40 to $5.50. The final count was to be 80,183, a crowd represented by fans of every walk of life.

At Boyle's, 2,900 police, firemen, plainclothes men and private ushers waited to handle the crush of spectators scheduled to arrive, setting up blockades four blocks away from the stadium, letting only properly accredited people into the menagerie.

As Carpentier entered the arena to the accompaniment of wild cheers, Up in section H, back in the $5.50 seats where the final additions were built, stadium started to sway.

"There was just a movement," an engineer who helped build the stands said "Let's not make a big thing out of it. There was a movement, a decided sway. But there was really never any danger of the stadium collapsing. None."

The people in the stands at the time were far from convinced. "Everybody stay down," one man shouted. Then he turned to a policeman. "If you police can't make them sit down, club them down."

Unaware of what was happening behind them, those in front watched Dempsey cutting Carpentier in the first round, getting stunned in the second, then mercilessly punishing the challenger in the third, before knocking him out in the fourth. Many were silent. Some cried.

The New York Times ran an eight-column banner on its front page the following day and filled six of its eight news columns with stories about the fight. The next 12 pages were filled with only fight stories and pictures. As if in apology, the staid old journal editorialized that same day, "The world may now gain its equipoise."Three days later a group of engineers checked the stadium and found it safe.

In the contest between Dempsey and Carpentier, the strength and power of Dempsey was too much for the Frenchman, who was knocked out in the fourth round, with a broken thumb.

Jersey City Makes History

The Dempsey-Carpentier bout in July 1921 is remembered by radio historians as one of the major occasions that helped usher in the "radio era" and mass communication. Developing into a trend in which big sporting events would be the catalyst of introducing new technology or expanded capability. Now with billions being able to access live streaming from around the world, on that day in July 1921 hundreds of thousands tuned in to hear the human voice beam out over the northeast United States for the first time.

Some more Background

It held approximately 80,000 fans and was built at a cost of $250,000. It was situated around Montgomery Street and Cornelian Avenue, on a plot of marshland owned by John F. Boyle. It stood for six more years, until Rickard had it torn down.

Tex Rickard, the promoter of the bout, initially wanted the fight to take place at the Polo Grounds in New York City. However, Nathan Lewis Miller, the governor of New York, opposed prizefighting and indicated that he did not want a Dempsey-Carpentier bout to be held in New York State

Construction started on April 28, 1921 and was completed a few days before the fight. The arena was initially due to hold 50,000 fans. However, the demand for the international extravaganza was so enormous that Rickard had to expand the arena to hold a capacity of around 80,000 to 90,000 fans. It had the greatest seating capacity of any amphitheater ever built.

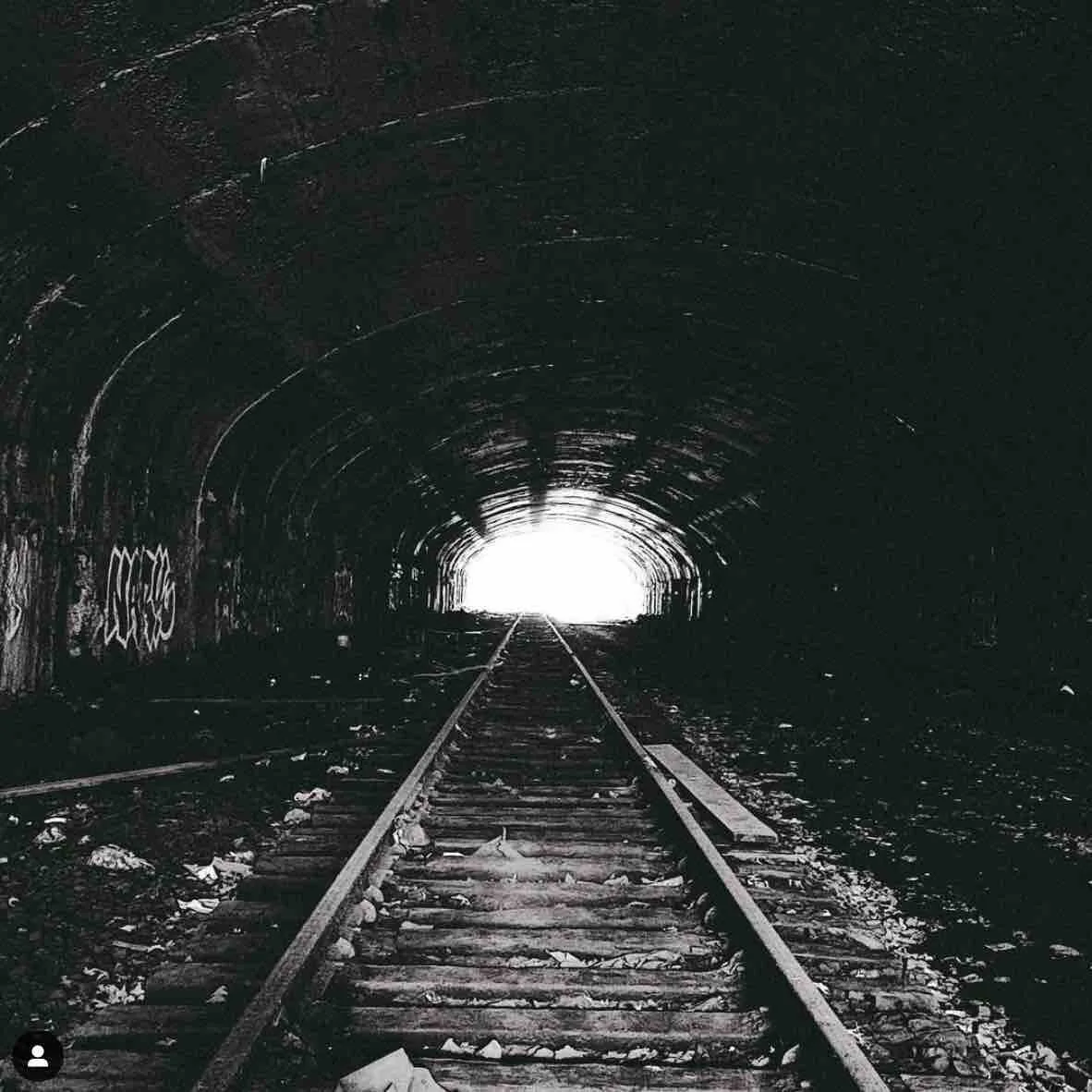

By 1927, 6 years after it was built, Rickard announced that the wooden arena would be demolished and in June 1927 the wrecking ball brought the short history of Boyle's Thirty Acres to an end.

Site of Boyle’s Thirty Acres Today

Today, Boyle's Thirty Acres are lost in the middle of a housing project, the only echo of their sporting past lying in the shouts of the kids from neighboring Ferris High School.By 1952, the site of Boyle's Thirty Acres had become a Jersey City housing project named Montgomery Gardens. After over 50 years of use, the project began to be emptied and the Jersey City Housing Authority planned to demolish the buildings in order to build mixed-use housing. Three of the six buildings were imploded in August 2015, and one was rehabilitated and converted to senior housing.

Read more about Jersey City’s History of Sports

The New Jersey Room at the Jersey City Public Library is a treasure-trove of historic and current information on New Jersey, Hudson County and Jersey City.